One of my soft new year’s resolutions for this year was, to borrow a phrase from Dan Pashman: read more and read more better. By that I mean: I wanted to read some of those books that have been sitting on the shelf, read new stuff, and read all of it with more care an intention. To that end, a few reflections:

Beloved, Toni Morrison

I read a book this year that’s been sitting on our shelves for years. It’s a modern day classic, part of the canon — to the extent I believe in such a thing. It being so well known, and well discussed in 2021, I knew quite a bit about the story going in: I knew it was a ghost story, haunted by deceased people as well as the history of the scene and characters. I managed to avoid spoilers, though this is the kind of book that, even if you know the most important details, the author’s choices in how to reveal them cannot be spoiled.

The book felt like a holding pattern, circling our destination, anticipating arrival, and growing gradually more concerned about what awaits you. Occasionally, we dive down into a scene, meet characters, get to know them better, and understand their motivations. All the while feeling a sinister subtext lurking around the corner. It all comes together suddenly and you nosedive. Their terrors become your own. It’s a slow burning horror story with shifting stakes and sympathies. Absolutely unlike any other book I’ve read.

I started reading this book around the time when it started to appear on banned book lists from GOP politicians. I definitely understand why this book makes people feel uncomfortable, but that’s no reason to ban it — or any book for that matter. It’s a book just as important as others common to the high school curriculum (or at least the library). It’s certainly more prescient and as much deserving of our youth — if not more — compared to books in high school curriculum: Rebecca, The Great Gatsby, All Quiet on the Western Front, Siddartha, etc. The drive to ban this book is rooted in racism and fear, nothing else.

The Underground Railroad, Colson Whitehead

This book was a striking representation of slavery as an institution and a lived experience. I think more so than any novel I’ve read before, it drives home exactly how slavery was institutionalized, and how it compromised every decision made throughout the country. Whitehead does this without any zero sum cynicism. Every character has clear motivations, details rooted in history, and every one of them are trapped in the grips of slavery in one way or another.

Whitehead shows how slavery and racism evolved together as the protagonist encounters the highly variable local laws and customs pertaining to runaway slaves, and how she manages to survive being Black in places where it is all but illegal. The idea of the Underground Railroad being a literal network of subterranean trains becomes an interesting device to illustrate the phenomenon of hasty migration under life-threatening duress, and the work required to protect and endure living along the way.

So, two for two where I’m years late to the party what’s next?

A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan

This book has been stalking me on our book shelf probably since it came out in 2011. I’d pick it up, read a couple chapters, then I’d get distracted by something like moving or travel, forget about it, and put it back on the shelf. Repeat that every couple of years for the last 10 and you basically have my relationship with this book.

Finally, in 2021, I got a chance to start and finish it. I’m really glad I did because it’s a lovely book, more than worthy of all the awards it won. It’s funny, stylistically interesting, and incredibly prescient. If you haven’t read it yet, grab a copy, get cozy, drink it in, and don’t spend too much time trying to reverse engineer Egan’s process for carefully stitching this book together. It’s a well crafted work of art we should all cherish.

After the Rain, Nnedi Okorafor (adapted as a graphic novel by John Jennings and David Brame)

Finally, a book published in 2021! This was the first graphic novel that arrived as part of a subscription from Lion’s Tooth in Milwaukee Danielle gave me for Christmas 2020. I believe it was the second graphic novel I’ve read, Watchmen being the first. This book demonstrates the lengths our pasts will go to haunt us. In some cases, it’ll go as far as hunting us down when we least expect it, trap us in its grips, and force us to reconcile.

It’s also a cross-cultural novel. Choima, our main character, is Nigerian-American and encounters these ghosts of her past in the US while visiting family in Nigeria. In some ways, After the Rain reminded me of Americanah, Chimanada Ngozi Adiche’s 2013 novel. It’s themes of migration and cultural code switching are similar, but the specificity of this story and the constraints of the medium allowed this story to be concise, precise, and just as consuming as a conventional (all-text?) novel would.

The illustrators, John Jennings and David Brame, were as new to me as the format but their resumes are well established. Their art complemented the text by adding a layer of complexity to the story and helping the reader understand Choima deeper and entrench sympathy for her.

Real Life, Brandon Taylor

Brandon Taylor didn’t write this book for me. He certainly didn’t write this book to end up on my list but here it is. I picked this book up by chance. We were in Salida, Colorado. I finished the book I brought along for the trip, and wandered into Book Haven looking for something to read. Taylor’s book was displayed on the new fiction table, saw the Booker Prize nomination, endorsements from Roxane Gay and Kiese Laymon, and picked it up.

I find myself thinking about this book constantly, months after I read it. As a white person somewhat familiar with largely-white academic and work settings, I often reflect on people like Wallace that I knew: how and when I behaved like almost every white person he encounters, and how I played into traps of erasure of a lot of Black and Brown students on my own campuses. In that regard, it was a sobering story.

This book challenges literary expectations of what kind of story can be told centered around a university campus. It’s not a coming of age story. Neither is it High Adventures in Partying and Mischief. Those are present but so is existential danger, trauma, sexuality, power, money, and meritocratic politics far more dominate in student life. And there’s real academic work happening in the background! Taylor dedicates significant effort toward showing the work Wallace does as a graduate student, and how brutally offensive neoliberal belittlement feels.

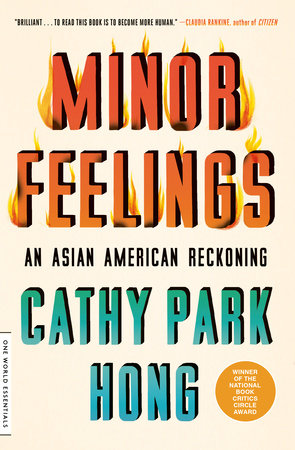

Minor Feelings, Cathy Park Hong

Something I think about a lot from our time living abroad is how I and my colleagues treated our young students at our academy. I remember one teacher in particular who shared a group of students with me. Our five through ten year-old students were tracked into levels based on their performance on a monthly standardized test in English.

We taught the lowest-scoring first graders together. He, and other teachers, would regularly call these children as idiots and worse epithets I won’t write here. Sometimes I still find myself asking these English teachers: How fucking fluent were you in a foreign language at the age of six?

Hong covers a lot of ground over a moving, precise, and pithy 224 pages including education, intersectionality, erasure of the voices and lives of Asian American people, and the harms of Western colonialism that continue to this day.

The Waiting, Keum Suk Gendry-Kim

There’s a certain kind of graphic novel that jumps out at me off the shelves at Lion’s Tooth, begging (daring) me to read it. The Waiting was one of them. This novel is drawn entirely in black and white, a choice on the author’s part that focused my attention on the character’s faces throughout the novel.

It’s a book set during the Korean War about a family marching south to seek safety. Ultimately, Gwija, the main character, ends up in Busan and the book is also about her clinging to hope that one day she might reunite with her family members who separated during the exodus.

Both Gendry-Kim and Cathy Park Hong want their readers to understand a fuller history of the Korean War. Perhaps the biggest myth is that the US forces were entirely on the side of the Korean people and without sin. The Waiting shows a throng of refugees taking shelter during an American bombing raid. Anybody out walking around in North Korea were assumed enemies and fair targets. In reality, they were refugees carrying whatever they could with them and their families to flee the war raining down upon them. People unaware of or disconnected from the global scope and details of the battle over their peninsula.

I remember coverage of the Inter-Korean family reunions while were in Korea. The stories we heard focused on the emotional meeting of people separated by decades and political stalemate. The format of a novel allows Gendry-Kim to go further, to help her readers understand the innate cruelty of separation, and how anguish collides with hope that you’ll see your child, spouse, sibling, aunt, etc. one more time before you die. The Waiting captures the perils and anxieties of separation-by-conflict and how people cope and thrive while they wait for relief.

I read a lot more books in 2021, after a few years of reading maybe one or two books a year. One thing that helped was not trying to read all the books. And instead, trying to read a diversity of books: Diversity in authorship, format, form, genre kept the reading interesting and helped me change modes after reading something particularly heavy or difficult. Graphic novels were a nice addition in this way. I can stay and linger on a scene in a graphic novel in a way you can’t in a text. I can examine the drawings closely, or hold the book at arms length and take in a spread, to better understand the author’s intent and the text’s deeper hermeneutics.

In 2022, I’m starting with In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado. So far, it’s a strong start to a year that, hopefully, will be stronger than the last.